Costanzo Preve (1943-2013) – Telling the truth about capitalism and about communism. The dialectic of limitlessness and the dialectic of corruption. Dire la verità sul capitalismo e sul comunismo. Dialettica dell’ illimitatezza, dialettica della corruzione.

Costanzo Preve

***

**

*

Gustav Klimt, Nuda Veritas,1899

Telling the truth about capitalism and about communism.

The dialectic of limitlessness and the dialectic of corruption

*

***

*

Dire la verità sul capitalismo e sul comunismo.

Dialettica dell’illimitatezza, dialettica della corruzione

Traduzione in inglese di Dimitri Papandreu

![]() Leggi e stampa il PDF di 20 pagine

Leggi e stampa il PDF di 20 pagine ![]()

This is a philosophical text, it is not recommended for people who lack patience and who do not read things many times over until they have understood them. In truth, this text originates from a reflection on a recent event in contemporary politics: the fact that in this November of 2011 the ex-communists of the transformist-metamorphosizing serpent PCI-PDS-DS-PD have become the main supporters of the externally imposed, ultra-capitalist economic commissar of Italy, Mario Monti, a Goldman Sachs man. But since I pulled the plug long ago on the manipulated and drugged conflict between Right and Left (and between the Party of the Bs and the Party of the anti-Bs), I will not waste time here addressing such nonsense as can be read about everyday in the circus of the media and seen every hour in the circus of the television.

Questo è un testo filosofico, sconsigliato a chi non ha pazienza e non legge le cose molte volte fino a che non le ha capite. In realtà parte da un recente accadimento dell’attualità politica, il fatto che gli ex-comunisti del serpentone metamorfico-trasformista PCI-PDS-DS-PD siano in questo novembre 2011 i principali sostenitori del commissariamento economico ultra-capitalistico dell’Italia da parte di Monti, uomo della Goldman Sachs. Dal momento però che ho staccato da tempo la spina nel conflitto drogato e manipolato Destra/Sinistra e del Partito dei B/Partito degli anti-B, non intendo perdere tempo con sciocchezze leggibili ogni giorno nel circo mediatico e visibili ogni ora in quello televisivo.

I will address instead a long-standing question, called dialectic. The dialectic is at the heart of a philosophical understanding of historical processes. I have written two words here: philosophy and history, or more precisely: philosophical understanding of historical events. We live in an age wherein it is taken for granted that economics can, by itself, sufficiently explain what really goes on in society; to economics can be added a touch of literature to shed light on individuals’ psychological conflicts. It would seem as though there were no place left for philosophy anymore.

Mi occuperò di un problema di lungo periodo, chiamato dialettica. La dialettica è al cuore della comprensione filosofica dei processi storici. Ho così scritto due termini: filosofia e storia, o più esattamente comprensione filosofica dei fatti storici. Viviamo in un tempo in cui si dà per scontato che per capire il lato sociale dell’attualità basti ed avanzi l’economia, integrata dalla letteratura per quanto riguarda i conflitti psicologici degli individui. Sembra che la filosofia non abbia nessuno spazio.

This writer thinks differently. Philosophy, if used well, can illuminate the historical present even better than can literature (which is still marvelous) and certainly better than can economics (which instead is miserable). But if used badly, philosophy is a waste of time. It would be better to contemplate enigmas, read detective novels, or go fishing.

Chi scrive la pensa diversamente: la filosofia, se bene usata (se male usata è una pura perdita di tempo, meglio l’enigmistica, i romanzi polizieschi e la pesca con la lenza) illumina il presente storico ancora meglio della letteratura (che pure è meravigliosa) e certamente meglio dell’economia (che invece è miserabile).

This philosophical text is divided into four parts; they are, respectively:

1. Introduction to the Dialectic

2. Capitalism: the Dialectic of Limitlessness

3. Communism: the Dialectic of Corruption

4. Open and Provisional Conclusions

Questo testo filosofico è diviso in quattro parti, rispettivamente:

1. Introduzione alla dialettica

2. Il capitalismo, la dialettica dell’illimitatezza

3. Il comunismo, la dialettica della corruzione

4. Conclusioni aperte e provvisorie

*

***

*

1. Introduction to the Dialectic

Philosophy, even when it seems most complicated, is always and exclusively concerned with questions of everyday life. Do not trust the people who tell you that philosophy is about things that are inaccessible to everyday good sense and to the common intellect. They are the philosophical equivalents of con artists and frauds. Philosophy, it is true, makes recourse to a specialized language in order to elaborate and systematize some of its questions (and in this it is like physics). But philosophy’s questions should nevertheless always remain accessible to the common intellect. Of the common intellect it is required only that it remain psychologically open to the possibility of understanding something new, and that it not close itself up like a clam.

1. Introduzione alla dialettica

La filosofia, anche quella apparentemente più complicata, parte sempre e soltanto dalla vita quotidiana. Diffidate da coloro che dicono che essa si occupa di cose inaccessibili al buon senso e all’intelletto comune. Costoro sono l’equivalente filosofico dei piazzisti e degli imbonitori. La filosofia però elabora e sistematizza in linguaggio necessariamente specialistico (simile in questo alla fisica) questioni accessibili anche e soprattutto all’intelletto comune. È sufficiente però che l’intelletto comune non si “chiuda a riccio”, ma accetti psicologicamente il terreno della possibile comprensione.

The dialectic is about how things change and do not stand still or remain the same over time (here I will spare the reader the history of the dialectic itself, although I have written a book on the subject). By “things” I do not mean shoes, stones or fish, but processes – the developmental processes of natural and social phenomena. In regards to natural phenomena, the main application of the dialectic is the theory of evolution, as is evident in the life sciences and also in geology and astrophysics. In regards to social phenomena, the dialectic must take into account a particular element that is nonexistent in natural phenomena, and that is the human will, which acts upon and changes the “given” world it finds before itself. In philosophy, this phenomenon is called “praxis” and it certainly wasn’t invented by Marx and the Marxists (come on!), the term was already being used by the ancient Greeks (particularly by Aristotle) and by the great German idealists of the early eighteen hundreds (particularly by Fichte).

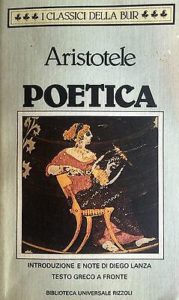

La dialettica (risparmio qui al lettore la sua storia, cui io però ho dedicato un libro apposito [Storia della dialettica]) parla di come le cose cambiano e non restano ferme e sempre uguali nel tempo. Per “cose” si intendono non le scarpe, i sassi, i pesci, ma i processi, e cioè i processi di sviluppo dei fenomeni naturali e sociali. Per quanto riguarda i fenomeni naturali l’applicazione principale della dialettica è la teoria dell’evoluzione, non solo per quanto riguarda le scienze della vita, ma anche la geologia e l’astrofisica. Per quanto riguarda i fenomeni sociali, la dialettica deve tenere conto di un elemento inesistente nei fenomeni naturali, e cioè la volontà umana, che progetta e modifica il mondo che si trova davanti “dato”. In filosofia, questo fenomeno si chiama “prassi”, e non se lo sono certamente inventati Marx e i marxisti (ma andiamo!), ma il termine c’era già presso gli antichi greci (particolarmente in Aristotele) e presso i grandi idealisti tedeschi di inizio ottocento (particolarmente in Fichte).

So, the dialectic is about change and mutation. But there are two different types of change. The first type of change is that which derives from the external action of a subject onto a passive object (for example, a sculptor chiseling a stone). The second type of change is that which derives from a change internal to the thing itself (for example, the process of aging, which occurs against our will).

Quindi, la dialettica parla del cambiamento e del mutamento. Ma ci sono due tipi diversi di cambiamento. Un primo tipo di cambiamento è quello che deriva da un’azione esterna di un soggetto su di un oggetto rimasto passivo (per esempio, il modellare una pietra con uno scalpello). Il secondo tipo di cambiamento è quello che deriva da un cambiamento interno alla cosa stessa (per esempio, l’invecchiamento, che avviene contro la nostra volontà).

The dialectic is the understanding of a process’s internal changes – and this understanding can be applied to processes that are historical and political. Politics, generally speaking, is only the superficial layer of history. If you try to understand history by beginning with politics, you will never understand it. If instead you try to understand politics by beginning with history, it is not certain that you will understand it but at least it’s worth a try.

La dialettica è la comprensione dei cambiamenti interni di un processo, comprensione applicata ai processi storici e politici. La politica, in prima approssimazione, è soltanto lo strato superficiale della storia. Se si parte dalla politica per capire la storia, non la si capirà mai. Se invece si parte dalla storia per capire la politica, non è detto che la si capisca sicuramente, ma almeno ci si può provare.

Because the dialectic is threatening to historically dominant groups it has been particularly maligned in university philosophy departments, which are generally nothing more than costly ideological apparatuses of these same dominant classes who want to make simple things appear complicated so that the general intellect cannot understand them (as do, by the way, university economics departments).

La dialettica, appunto perché pericolosa per i gruppi storicamente dominanti, è diffamata in particolare nelle facoltà universitarie di filosofia, che sono in generale costosi apparati ideologici delle stesse classi dominanti, e devono far diventare complicate le cose semplici, in modo che l’intelletto comune non le capisca (come fa, del resto, la facoltà universitaria di economia).

There is not the space here, nor the need, to enumerate in detail all of the many variants of defamation the dialectic has endured. I will summarily review only the three main variants (although there are many others):

Non vi è qui lo spazio, e neppure la necessità, per enumerare in dettaglio tutte le numerosissime varianti della diffamazione della dialettica. Ricordo qui solo sommariamente le tre principali (ma ce ne sono molte altre):

(1) The dialectic is an instrument of philosophers, but philosophy itself is not a trustworthy form of knowledge of the real. Only science is trustworthy, and science does not utilize the dialectic but only common logic, which it applies to mathematics and to controlled experiments. In three thousand years philosophers have never been able to agree on anything, lost as they are in their endless chatter about things they cannot prove. Science, on the other hand, has succeeded in establishing precise protocols for determining truth and for rejecting false hypotheses.

In response to this objection the following can be said: Even if it is granted that science does not use the dialectical method (which in fact it does according to eminent scientists) this is only because the specific character of its object does not require it. The object of the natural sciences (astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, genetics, geology, etcetera) is different from the object of the human social sciences wherein the subjective agencies of individuals and groups intervene and exert a fallback, dialectical effect on the subjective agencies of others with whom they may be in opposition and/or in agreement.

(1) La dialettica è uno strumento dei filosofi, ma la filosofia non è una conoscenza affidabile del reale. Soltanto la scienza lo è, e la scienza non utilizza la dialettica, ma soltanto la logica comune, applicata alla matematica e all’esperimento controllato. In tremila anni i filosofi non sono mai riusciti a mettersi d’accordo con le loro chiacchiere interminabili ed indimostrabili, mentre la scienza invece ha precisi protocolli di verificazione e di falsificabilità delle ipotesi eventualmente errate.

A questa obiezione si può rispondere che, anche ammesso che la scienza non utilizzi mai il metodo dialettico (ma insigni scienziati sostengono che invece lo usa), questo riguarda solo l’oggetto delle scienze della natura (astronomia, fisica, chimica, biologia, genetica, geologia, eccetera), mentre nella storia sociale umana interviene la soggettività progettuali individuale e collettiva, che retroagisce dialetticamente con altri progetti opposti e/o convergenti.

(2) The dialectic is an instrument of sophistry used to justify and explain everything and anything that happens, including acts of human evil and viciousness ranging from Auschwitz to Hiroshima, and from Hitler to Stalin. If history is indeed endowed with an inexorable necessity, it then becomes possible to justify everything as being a product of an almost “natural” historical necessity.

In response to this objection the following can be said: This would be true if history were a branch of the natural sciences characterized by modal categories of necessity (as though it were physics, with its equations for a falling body), but it is not. The dialectic is simply there to assist in the understanding of why a certain process, begun with certain intentions, reaches an end that turns out to be the exact opposite of what was expected. The great Italian philosopher Vico spoke of the “heterogony of ends” in regards to this occurrence, but even if you are not familiar with the history of philosophy you can still intuit this by reflecting on the experiences of everyday life, wherein we often find ourselves pursuing certain projects or goals that end up becoming the exact opposite of what we had imagined or wanted.

(2) La dialettica è uno strumento sofistico per giustificare tutto ciò che avviene, ed in questo modo si può sempre giustificare e spiegare tutto, compreso il male e la malvagità umana, da Auschwitz a Hiroshima, da Stalin a Hitler. Se infatti alla storia viene attribuita una inesorabile necessità storica, allora diventa possibile giustificare tutto come prodotto di una necessità storica quasi “naturale”.

A questa obiezione si può rispondere che questo sarebbe vero se la storia fosse una branca delle scienze naturali caratterizzate dalla categoria modale delle necessità (tipo caduta dei gravi in fisica) ma questo non è. La dialettica non intende affatto giustificare tutto, al contrario. La dialettica aiuta semplicemente a capire il perché un certo processo, partito con certe intenzioni, si è rovesciato alla fine nel suo esatto contrario. Il grande filosofo italiano Vico ha parlato in proposito di “eterogenesi dei fini”, ma anche chi non conosce la storia della filosofia ha sperimentato il fatto quotidiano che spesso ci si ripropone una cosa o un progetto, e si ottiene l’esatto contrario, che non avremmo mai voluto.

(3) The dialectic is a form of religion for intellectuals who imagine the world as being “alienated” or upside down, consequently they think the world needs to be turned right side up. In reality the world is not at all upside down and therefore it has no need of being turned right side up. Intellectuals such as these should instead try their best to accept the world for how it actually is. The Marxist dialectic in particular, which conceives of capitalism as an alienated world standing on its head, tends to imagine that once upon a time at the beginning of history there existed a normal world standing properly on its feet – and now, at the end of history, that lost world stands to be restored. This is nothing other than the transcription into a sophisticated philosophical language of the monotheistic religious concept of an original Terrestrial Paradise that was lost due to God’s punishment of Original Sin.

In response to this objection the following can be said: The dialectic is not at all concerned with the imaginary restoration of a lost Origin that will be accomplished through the work of a demiurgical Subject who is actually the social-historical manifestation of the Body of Christ (this imaginary restoration would occur at the preordained Final End of History, and would correspond to communism – but this would be a communism for fools). Instead, the dialectic is concerned with analyzing historical processes from a point of view that is internal to the processes themselves, and not external to them.

(3) La dialettica è una forma di religione per intellettuali, che si inventano un mondo “alienato” a testa in giù da raddrizzare, laddove il mondo reale non è affatto a testa in giù, e quindi non deve essere affatto raddrizzata, ma va preso così com’è nel migliore modo possibile. In particolare la dialettica marxista, presupponendo che il capitalismo è un mondo alienato da raddrizzare, immagina che ci sia stato un tempo, all’origine della storia, un mondo diritto, normale, che si tratta di restaurare. Si tratta della trascrizione in linguaggio filosofico sofisticato nella concezione religiosa monoteistica per cui c’è stato all’origine un Paradiso Terrestre, perduto a causa di un Peccato Originale punito da Dio.

A questa obiezione si può rispondere che la dialettica non si occupa di una pretesa ed inesistente restaurazione di una Origine nel frattempo perduta ad opera di un Soggetto demiurgico, che non sarebbe altro che la manifestazione storico-sociale del Corpo di Cristo, in vista di un Fine Ultimo della Storia già prefissato (il comunismo, appunto, ma sarebbe un comunismo per imbecilli), ma di un’analisi degli sviluppi storici da un punto di vista interno al processo stesso, e non invece esterno.

Our discourse has just gotten started, but for now I will bring it to an end. In the next parts of the text I will “apply” the discourse to two phenomena that are dialectically interconnected, but which I will address separately: the dialectic of capitalism characterized by limitlessness, and the dialectic of communism characterized by corruption. I am referring obviously to real existing capitalism and not to its utopian representation wherein the harmony of the market is majestically arranged by the market’s own “invisible hand,” and I am referring to real existing communism and not to its idealized representation issued forth from the hand of Marx.

It is impossible to write the things I have in mind without irritating someone. But if a philosopher is frightened by the possibility of causing irritation and the defamatory gossip that might ensue, then he would be better off to stop philosophizing altogether and open a popcorn stand.

Il discorso sarebbe appena cominciato, ma possiamo per ora terminarlo qui, in quanto verrà “applicato” a due fenomeni, trattati separatamente, ma in realtà dialetticamente interconnessi, la dialettica del capitalismo, caratterizzata dalla illimitatezza, e la dialettica del comunismo, caratterizzata dalla corruzione. Parlo ovviamente del capitalismo realmente esistente, e non di quella rappresentazione utopica di esso caratterizzata dalle presunte armonie del mercato e dalla “mano invisibile” del mercato stesso, e del comunismo realmente esistito, e non di quella rappresentazione idealizzata presa da Marx.

Impossibile scrivere queste cose senza irritare qualcuno. Ma se il filosofo si spaventasse per l’eventualità dell’irritazione e del gossip diffamatorio, tanto varrebbe smettere di filosofare ed aprire una baracchetta di pop-corn.

***

2. Capitalism: the Dialectic of Limitlessness

Before being a society bound by the reproduction of strict economic laws, capitalism is a social-historical process characterized by a specific dialectic. That is the dialectic of limitlessness, which is characterized by the impossibility of respecting any limit set by the bounds of religion, philosophy or politics. Here I assume that the reader is already familiar with the history of the first era of capitalist globalization from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries (studied by Wallerstein), with the economic periodization of capitalism (studied by Giovanni Arrighi), with the second era of imperialist globalization of the late nineteenth century, and with the third, current era of capitalist globalization (studied in particular by David Harvey). I will limit myself, deliberately, to only the philosophical-dialectical side of the problem.

2. Il capitalismo: la dialettica dell’illimitatezza

Prima di essere una società dominata dalla riproduzione di vincoli economici ben precisi, il capitalismo è un processo storico sociale caratterizzato da una specifica dialettica. Si tratta della dialettica della illimitatezza, caratterizzata dalla impossibilità di rispettare un limite definito in via religiosa, filosofica e politica. Qui diamo per scontata nel lettore la conoscenza storica della prima globalizzazione capitalistica mondiale (studiata da Wallerstein) fra il Quattrocento ed il Seicento, della periodizzazione economica del capitalismo (studiata da Giovanni Arrighi), della seconda globalizzazione imperialista di fine Ottocento, e dell’attuale terza globalizzazione capitalista (studiata in particolare da David Harvey). Mi limiterò invece volutamente al solo aspetto filosofico-dialettico del problema.

The dialectic of limitlessness was already studied most admirably by the ancient Greeks, and their study of it is in fact philosophically complete. But the ancient Greeks could obviously not apply it to a capitalism that did not yet exist. Instead, they applied it to the limitless accumulation of monetary wealth and tyrannical, despotic political power that threatened the communitarian reproduction of the polis. The reader should not bother looking for these things in the usual history of philosophy textbooks, which are written for the sole purpose of de-historicizing and de-socializing their subject matter. Textbooks make it seem as though somewhere in the distant past the ancestors of our science departments got together and began debating whether the world was born from water or from air, whether voids actually exist or do not exist, whether the world was created by chance (Odifreddi’s true ancestors!) or by a superior mind (Ratzinger’s true ancestors!), etcetera, in an orgy of stupidity.

La dialettica della illimitatezza fu già studiata in modo mirabile (e di fatto filosoficamente completo) dagli antichi greci, che ovviamente non potevano applicarla ad uno ancora inesistente capitalismo, ma la applicavano all’accumulazione illimitata di ricchezze monetarie e di potere politico tirannico e dispotico che minacciava la riproduzione comunitaria della polis. Il lettore non cerchi di capirci qualcosa con i consueti manuali di storia della filosofia, costruiti sulla base della destoricizzazione e della desocializzazione. Sembra che ad un certo punto alcuni precursori delle facoltà scientifiche abbiano cominciato a dire che il mondo nasce dall’acqua o dell’aria, che c’è il vuoto oppure non c’è, che il mondo è stato fatto a caso (dei veri precursori di Odifreddi!), oppure che è stato fatto da una mente superiore (dei veri precursori di Ratzinger!). Eccetera, in un’orgia di stupidità.

What nonsense. The first philosophers were first of all communitarian legislators who, in order to gain credibility and influence among their fellow citizens, had to appear as learned experts of nature (physis) given that for the Greeks there existed no pact with God and therefore no prophets or Messiahs, whether bearded or clean-shaven, or human or divine. They proposed communitarian laws (nomoi) based on a social calculation of what constituted the right distribution of goods (logos); their laws met the standard of justice (dike) because they applied the principle of the just measure (metron).

Sciocchezze. I primi filosofi erano prima di tutto legislatori comunitari, che per rendersi autorevoli e credibili presso i loro concittadini in termini di proposte legislative comunitarie (nomoi), rette da un calcolo sociale della buona distribuzione dei beni (logos), che per andare incontro alla giustizia (dike) dovevano prima di tutto applicare la giusta misura (metron), dovevano apparire come conoscitori della natura (physis), visto che per i greci non esisteva nessun patto con Dio, e quindi non ci potevano essere profeti e Messia, non importa se barbuti o rasati, umani o divini.

Starting from nature, it seemed clear that the limit was a principle of order (taxis) whereas the limitless (apeiron) was a principle of uncontrollable destructiveness. If this were true in nature then it must also be true in society, particularly in regards to the limitless power of wealth. Don’t imagine that you can find any of this in philosophy textbooks. I have assigned them to students myself for 35 years, which is like Galileo being forced to assign geocentric textbooks, or Darwin being forced to assign creationist ones. Oh the things we won’t do to make it to retirement!

Partendo dalla natura, appariva chiaro che mentre il limite è un principio di ordine (taxis), l’illimitato (apeiron) è invece un principio distruttore ed incontrollabile, e così come lo è in natura, così lo è anche nella società (e cioè il potere illimitato delle ricchezze). Non crediate di poter trovare queste cose nei manuali di filosofia. Li ho adoperati io stesso per 35 anni, ed è come se Galileo fosse stato costretto a servirsi di un manuale geocentrico e Darwin di un manuale fissista. Ma cosa non si fa per la pensione!

Pythagoras was the first to numerically systematize the principle by which the limit is better than the limitless. Plato was simply one of Pythagoras’ Athenian pupils well-versed in Socratic dialogue. Parmenides was the first to use the (apparently abstract, but in reality quite concrete) term Being to denote the metaphorically permanent, eternal observance of the good Pythagorean political laws that were capable of impeding the destructive irruption of wealth, which he metaphorically denoted with the term Nothingness (and which high school and university textbooks mistake for a pneumatic void). And I could go on. But what matters here is to have understood the essential: when the great philosophers of Greek antiquity were confronted with processes of corruption and social unraveling caused by monetary wealth and debt slavery (just as we today are confronted with new forms of capitalist debt slavery) they had already dialectically understood that without a limit imposed by the human will and inspired by the principle of the just measure, there would be no way to stop and oppose (katechon) the destructive power unleashed by the limitless.

Pitagora fu il primo a sistematizzare numericamente il principio per cui il limite è migliore dell’illimitato. Platone non ne fu che un allievo ateniese passato per il dialogo socratico. Parmenide fu il primo che con il termine (solo apparentemente astratto, ed è in realtà concreto) di Essere intese indicare la metafora del mantenimento permanente “eterno” di una buona legislazione politica pitagorica capace di impedire l’irruzione distruttiva della ricchezza (metaforizzata correttamente con il termine di Nulla, che i manuali liceali ed universitari scambiano per il vuoto pneumatico). E potremo continuare. Ma ciò che conta è capire che il grande pensiero filosofico greco, di fronte ai processi di corruzione e di dissolvimento portati dalla ricchezza monetaria e dalla schiavitù per debiti (esattamente lo stesso problema cui siamo oggi di fronte, una nuova versione capitalistica della schiavitù per debiti), aveva già dialetticamente capito che senza un limite, posto dalla volontà umana ispirata dalla misura, non c’era modo di fermare e di opporsi (katechon) allo scatenamento delle potenze distruttive dell’illimitato.

We can be brief in surveying the historical period extending from 300 before Christ to 1700 after Christ. But since Christianity lies at the core of this period, and Christianity is a historical phenomenon as big as the Himalayas, we cannot exactly “leap” over its philosophical import. For Christians, only God is limitless and infinite, whereas humans are by nature “finite.” But the symbolic governance of human finiteness is delegated to a particular power: the Christian churches. The churches (regardless of their bloody divisions) make human finiteness commensurable with political class relations that defend first ancient slavery, then feudalism, then seigneurialism, then absolutism, and finally capitalism. Although God is supposed to be “neutral” regarding the economy, he just so happens to be almost always on the side of the ruling classes. Yet symbolically, God also acts as a limit to the limitless arrogance of these very same ruling classes, who have by their sides not economists but priests to whom they must confess. We are not dealing with pure hypocrisy here, even though the hypocritical aspect is provocatively dominant and has always nurtured successive waves of simple-minded, “secular” anticlericalism. But the fact still remains that the belief in God was in itself a limit, albeit often a fragile one, to the tendencies to limitlessness of money and power.

Facciamola corta sulla storia dal Trecento avanti Cristo al Mille e Settecento dopo Cristo. Dal momento però che in mezzo c’è il cristianesimo, che è un fenomeno storico grande come l’Himalaya, non posso “saltare” del tutto il suo “risvolto” filosofico. Per i cristiani l’unico illimitato ed infinito è Dio, mentre gli uomini per loro stessa natura sono “finiti”. Ma la gestione simbolica di questa finitezza è delegata ad un potere particolare, le chiese cristiane (prescindo qui dalle loro divisioni sanguinose), che commisura questa finitezza ai rapporti politici di classe che di volta in volta difende, prima schiavistici, poi feudali, poi signorili, poi assolutisti ed infine capitalistici. Dio è presupposto “neutrale” rispetto all’economia, ma guarda caso è quasi sempre a fianco dei dominanti. Dio però è simbolicamente anche un limite all’illimitata prepotenza dei dominanti stessi, che infatti a fianco non hanno economisti, ma confessori. Non si tratta di pura ipocrisia, anche se l’aspetto ipocrita è provocatoriamente dominante, ed ha sempre nutrito tutti i facili anticlericalismi “laici” successivi. Il fatto però di credere in Dio era di per sé un limite, sia pure spesso fragile, alle tendenze alla illimitatezza del denaro e del potere.

Capitalism cannot be born on the basis of an external limitation acting on the economy – it especially cannot be born philosophically in this manner. Therefore as a matter of principle, capitalism is born as philosophically limitless. The accumulation of capital must conceive of itself as being theoretically limitless, even while it contemplates the ecological limits of nature and the limits imposed by human morality. Bearing this in mind, we may now examine the philosophical birth of capitalism’s new, more restricting way of conceiving of limits.

Il capitalismo non può nascere, soprattutto filosoficamente, sulla base di una limitazione esterna all’economia stessa. Esso nasce quindi come filosoficamente illimitato in via di principio. L’accumulazione del capitale deve pensarsi come teoricamente illimitata, sia pure in presenza dei limiti ecologici della natura e dei limiti dovuti alla moralità umana. Bisogna quindi prestare attenzione alla nascita filosofica del nuovo tipo di limitatezza del capitalismo.

For the sake of saving time I will skip over the interesting covenant between capitalism and Calvinism, which in my opinion is greatly overestimated. I will turn the reader’s attention instead to the seventeen hundreds. At around this time there existed three theoretical “limits” to what would otherwise be the unrestrained dominance of the economy. They were, in order of importance: a religious limit (God), a philosophical limit (natural law, or jusnaturalism), and a political limit (the social contract, or contractualism). Yet once the nascent discipline of political economy sought to establish itself as a completely self-contained and self-referential entity, independent of any external foundation that might limit it in any way, it became necessary to dispose of God, of natural law, and of the social contract. This remarkable enterprise was undertaken by a pair of Scotsmen, David Hume and Adam Smith. Rather than go into details here, let me make sure the reader has understood the heart of the matter.

Intorno al Settecento circa (risparmio qui le pur interessanti promesse del rapporto fra capitalismo e calvinismo, a mio avviso largamente sopravvalutate) i tre “limiti” teorici al dominio incontrollato dell’economia erano nell’ordine un limite religioso (Dio), un limite filosofico (il diritto naturale, o giusnaturalismo) ed un limite politico (il contratto sociale, o contrattualismo). Perché l’economia politica potesse autofondarsi su se stessi integralmente, senza alcun bisogno di fondazione esterna che la limitasse, bisognava disfarsi dell’ordine di Dio, del diritto naturale e del contratto sociale. Chi compì questa notevole impresa fu una coppia di scozzesi, David Hume ed Adam Smith. In questa sede, non posso scendere nei particolari, e devo accontentarmi del cuore del problema.

I repeat: the heart of the matter is political economy’s act of self-foundation, its declaration of independence from any “limits” imposed by factors external to the economy itself, such as God (religion), natural law (philosophy), or the social contract (politics). Without being subject to any “external” limitations, and appearing to be completely self-sufficient, self-perpetuating and sovereign, the economy assumes the symbolic status of an absolute power. We are dealing here with a conceptual totalitarianism that not even religions have dared to attempt (God is in fact always a “limit” to human behavior). Leaving aside for now the names and dates, I will get right to the core of political economy’s reasoning.

Ripeto: il cuore del problema è l’autofondazione dell’economia politica su se stessa, senza dipendenze (e cioè senza “limiti”) da parte di fattori esterni all’economia stessa, come Dio (religione), diritto naturale (filosofia) o contratto sociale (politica). Perché l’economia possa avere un potere simbolico assoluto, non deve essere limitata da niente di “esterno”, ed apparire come completamente autosufficiente e sovrana su se stessa. Si tratta di un totalitarismo concettuale che persino le religioni non hanno mai osato sostenere in questa forma (Dio è infatti sempre un “limite” per i comportamenti umani). Qui lascio perdere i nomi, e giungo al nocciolo del ragionamento.

The economy is sovereign because it is based on human nature, which is seen to exhibit a spontaneous propensity and an innate inclination for the exchange of goods and services between buyers and sellers. This spontaneous behavior has no need of any external foundation, be it God, or natural law, or the social contract. Let’s follow the reasoning further: political economy is skeptical regarding God, and not atheist or materialist. It has no need to assert that God does not exist, or that priests are shamans and sorcerers who take advantage of ignorant people’s superstitions. This the economists can leave to the fanatical secularists, and to their tattered, latter-day, plebeian followers: the atheist communists, who in the place of God proclaim another God that is even more non-existent than the first one, namely History intended as the irreversible march of progress. It suffices the economists that God does not interfere with the harmonious workings of the economy, and that he contents himself with only the domain of individual morality, particularly as it regards sex. It is really the height of idolatry to think that God, with all of the many things he presumably has to do, should be primarily and exclusively concerned with extramarital sex (though I do not dream to suggest that its ethical significance is purely and exclusively “private”). Anyhow, what matters is that God does not stick his otherworldly nose into the workings of the economy.

L’economia è sovrana, perché si basa sulla natura umana, che viene vista come portatrice di una tendenza spontanea e di un’abitudine innata allo scambio fra le attese del venditore e quelle del compratore. Questo meccanismo spontaneo non ha bisogno di nessuna fondazione esterna, che sia Dio, il diritto naturale o il contratto sociale. Seguiamo il ragionamento. Per quanto riguarda Dio, l’economia politica è scettica, e non atea o materialistica. Non c’è nessun bisogno di affermare che Dio non esiste, e che i preti sono sciamani e stregoni che approfittano delle superstizioni degli ignoranti. Questo gli economisti lo lasciano ai laicisti fanatici, ed alla loro versione plebea e stracciona posteriore, i comunisti atei che al posto di Dio mettono un altro Dio ancora più inesistente, la Storia intesa come fatalità irreversibile del progresso. Basta dire che Dio non può interferire nelle armonie economiche, e deve accontentarsi al massimo del regno della morale individuale, particolarmente sessuale. E’ veramente il massimo dell’idolatria pensare che Dio, con tutte le cose che presumibilmente ha da fare, debba occuparsi prioritariamente ed esclusivamente di scopate extra-matrimoniali (il cui aspetto etico di rilevanza non puramente e esclusivamente “privata” non mi sogno comunque di negare). In ogni caso, ciò che conta è che Dio non ficchi il suo naso ultraterreno nei meccanismi economici.

As for philosophy, it is known for not being able to empirically prove any of the things that it asserts. This was the case with the doctrine of natural law, and it continues to be the case with the German idealist system, with Marx’s theory of alienation, with Nietzsche’s Superman-inspired delirium, with Heidegger’s pessimism, and with Adorno’s, Lyotard’s and Sloterdijk’s pessimistic disenchantment, etcetera. Therefore, it would be better if philosophy did not bother people about things that actually matter, like the economy. Hume even recommends burning all philosophy books that claim to speak of “truth,” and indeed, if the only real truth is the GDP and the markets’ judgment then what is the use of talking about Being when it is completely indemonstrable? As for the social contract, Hume considers the generally held belief that it is “caused” by natural law and that it in turn “causes” human society. This belief was supported by an interpretation from the “Right” by Hobbes, from the “Center” by Locke, and from the “Left” by Rousseau. But in truth of fact, the social contract’s chain of causality cannot be proven either. Therefore it is unfeasible to establish a society’s economy on the basis of a philosophical premise that is indemonstrable and nonexistent (Philosophy? Ha-ha-ha!) And as if that were not enough, it is also unfeasible to postulate a stable preliminary definition of subjectivity, since that which is called the “subject” is really nothing but a fickle flux of sensations and impressions. (On this same basis, a century later, Nietzsche maintained that the subject was merely an energy flow of the will to power, and yet only a hallucinatory, mustachioed person could think that by holding this definition of the subject he was being anti-bourgeois!).

Per quanto riguarda la filosofia (a quei tempi il diritto naturale, e poi successivamente il sistema idealistico tedesco, la teoria dell’alienazione di Marx, il delirio superomistico di Nietzsche, il pessimismo di Heidegger, fino al disincanto pessimistico di Adorno, Lyotard, Sloterdijk, eccetera), è noto che essa non può dimostrare empiricamente niente di quanto afferma, e quindi è meglio che non rompa le scatole su cose serie come l’economia. Hume consiglia addirittura di bruciare tutti i libri di filosofia che pretendano di parlare della “verità”, ed in effetti se la sola verità è il PIL ed il giudizio dei mercati, a che serve parlare dell’Essere, che è del tutto indimostrabile? In quanto al contratto sociale, Hume ritiene che molti credono che esso sia “causato” dal diritto naturale, “causi” la società umana e ne sia una interpretazione (di “destra”, Hobbes, di “centro”, Locke, o di “sinistra”, Rousseau), ma la causalità non esiste neppure, ed in ogni caso non si può fondare la società economica sulla base di una premessa indimostrabile ed inesistente, come la filosofia (la filosofia? Ha-ah-ah!). Come se questo non bastasse, non si può neppure postulare una soggettività stabile preliminare, in quanto ciò che viene chiamato “soggetto” non è che un flusso mutevole di sensazioni e di impressioni (Nietzsche, su questa base, sostenne un secolo dopo che il soggetto non era che un flusso energetico di volontà di potenza, e solo un baffuto allucinato poteva pensare di essere così anche anti-borghese!).

May the reader take a deep breath. In the manner just described, capitalism established for itself an absolutely limitless potential that was unbound by any of the external “limits” of religion, philosophy and politics. The fatal “market judgment” of today, to which various “communists” have submitted (except for small marginalized groups of fundamentalist true believers), is nothing other than the dialectical development of capitalism’s self-founding premise.

Il lettore respiri profondamente. In questo modo, il capitalismo è fondato su di una illimitatezza potenziale assoluta, perché non esistono “limiti” esterni, come la religione, la filosofia e la politica. L’attuale e fatale “giudizio dei mercati”, cui si sono sottomessi i vari “comunisti” (ad eccezione di piccoli gruppi marginali di credenti fondamentalisti), non è che uno sviluppo dialettico di questa premessa autofondata.

Capitalism is therefore not at all “conservative” as it was believed to be for a century by the stupidest intellectual emulsion in the solar system: the culture of the Left. Quite to the contrary, it is a revolutionary force, but one that I would define as being fundamentally nihilistic. Capitalism’s being simultaneously revolutionary and nihilistic holds a connotation that is important to grasp, because it conceptually determines the theoretical framework through which capitalism is understood. Capitalism is revolutionary, as Marx had already noted, because it revolutionizes and destroys all preceding ideological, economic, political and social systems with a formidable single-mindedness. Its one and only goal is to promote the “infinite” and unfettered (apeiron) expansion of the commodity form over every minute aspect of individual and community life. Nothing can get in the way of this goal, neither the remnants of feudalism nor the remnants of the proletariat or the bourgeoisie (the most foolish error of the Leftist tradition has been to always identify the bourgeoisie directly with capitalism, which means to identify a collective historical subjectivity with an anonymous and impersonal process of reproduction). But at the same time capitalism is nihilistic, because its unlimited expansion of the commodity form is exactly that which was referred to in Greek philosophy, ever since Parmenides, as Nothingness. In point of fact, today’s capitalists are not even “bourgeois” anymore, although once upon a time they were. Today they are only “character masks” (to use Marx’s term). They are only the roles performed by actors in a social script; they are only the strategic agents of an anonymous and impersonal mechanism of capitalist reproduction to which contemporary philosophy has already given many names (Weber’s iron cage, Heidegger’s technical dispositif, etcetera). The Italian scholar who has best understood this is Gianfranco La Grassa (and for this very reason he has been silenced by the politically correct “Left”). La Grassa is worth your while to read, if you can get over his disgusting expectorations against philosophy and humanism, which are caused by residual deposits of ideological extremism from the 1970s.

Il capitalismo non è quindi per nulla “conservatore”, come lo ha creduto per un secolo l’emulsione intellettuale più stupida del sistema solare, e cioè la cultura di sinistra. Al contrario, esso è una forza rivoluzionaria, che definirò però un rivoluzionarismo nichilista. È bene comprendere questa connotazione, perché essa delimita concettualmente i confini teorici della sua comprensione. Esso è rivoluzionario, come aveva già capito Marx, perché è rivoluzione e distrugge tutti i sistemi ideologici, economici, politici e sociali precedenti, in quanto non si ferma davanti a niente, non importa se sia un residuo feudale, proletario o borghese (l’errore più stupido della tradizione di sinistra è sempre stato quello di identificare la borghesia con il capitalismo, e cioè una soggettività storica collettiva con un processo anonimo riproduttivo impersonale), in quanto la sua sola finalità è l’allargamento “infinito” ed indeterminato (apeiron) della forma di merce a tutti gli ambiti possibili di vita individuale o associata e comunitaria. Esso è nichilista, perché il semplice allargamento illimitato della forma di merce è esattamente ciò che nella filosofia greca, a partire da Parmenide, era connotato come il Nulla. I capitalisti, infatti, oggi non sono più neppure “borghesi”, anche se un tempo lo erano. Oggi sono solo delle “maschere di carattere” (Marx), dei ruoli sociali, degli agenti strategici della riproduzione capitalistica, meccanismo anonimo ed impersonale che nella filosofia contemporanea ha già avuto molti nomi (gabbia d’acciaio in Weber, dispositivo tecnico in Heidegger, eccetera). Lo studioso italiano che lo ha capito meglio (e per questo è stato silenziato dalla “sinistra” politicamente corretta) è stato Gianfranco La Grassa, e conviene leggerlo, se si riesce a superare il senso di ripu-gnanza delle sue espettorazioni contro la filosofia e l’umanesimo, residuo di depositi ideologici estremistici degli anni Sessanta del Novecento.

The dynamic of limitlessness holds us thoroughly in its grasp today. The various Lagardes, Montis, etcetera, who we see are only puppets, character masks. The dialectic allows this process to be understood very clearly. We obviously need a “limit,” yet we suffer from the lack of one. The grotesque, impotent and philosophically illiterate movements that serve only a testimonial function (pacifism, alter-globalization, Indignados, etcetera) cannot convince me that they in fact are “limits.” These people couldn’t even put a limit on boiling water inside a coffeemaker. The same applies to the labor unions, whose impotency is plastically manifested in the drums and whistles that accompany their deambulatory rituals. The movement of twentieth-century historical communism (1917 – 1991), now defunct for at least twenty years as a world-historical factor, was instead a real limit (katechon), although a very weak one. I am referring obviously not to the charlatan snobs of Leftist salons, but specifically to the Communist States with planned economies and extensive geopolitical power.

Attualmente siamo in preda alla dinamica dell’illimitatezza. I vari Lagarde, Monti, eccetera, non sono che fantocci, maschere di carattere. La dialettica permette di capire bene questo processo. Ci vuole, ovviamente, un “limite”, ma soffriamo di questa mancanza. Non mi raccontino che sono “limiti” i grotteschi movimenti impotenti, testimoniali e filosoficamente analfabeti (pacifismo, altermondialismo, indignati, eccetera). Costoro non potrebbero limitare neppure il bollire dell’acqua per il caffè. Lo stesso si può dire dei movimenti sindacali, la cui impotenza si manifesta plasticamente nei tamburi e nei fischietti dei loro riti deambulatori. Il movimento del comunismo storico novecentesco (1917-1991), oggi defunto da almeno un ventennio come fattore storico mondiale, è invece stato un limite vero (katechon), sia pure debolissimo. Non parlo ovviamente dei ciarlatani snob dei salotti di sinistra, ma proprio degli Stati comunisti ad economia pianificata ed a estensione geopolitica.

But they exist no more. Was their end caused by a betrayal? Don’t be silly! Their end came as the result of an internal dialectic, which I will now try to summarily describe.

Ma questi sono finiti. Per tradimento? Ma non diciamo sciocchezze! Sono finiti per una dialettica interna, che cercherò sommariamente di descrivere adesso.

***

3. Communism: the Dialectic of Corruption

There is a usual way of exorcizing the problem of communism’s internal dialectical corruption, and that is by making a distinction between the “real communists,” which means those who have subjectively remained so, (amongst whom, if we wish to use this troglodytic term, I include myself) and the “fake communists,” or ex-communists (like Gorbachev, Yeltsin, D’Alema, Veltroni, Napolitano, etcetera). In this way, the problem of communism’s irreversible corruption as a historical phenomenon is continually deferred so as not to upset the last of the gullible believers who need to be constantly reassured by the theory of the traitor’s subjective betrayal (the atheist equivalent of the theory of sin and the weakness of the flesh for religious believers). But I will choose another way of addressing the problem. From a strictly philosophical point of view I am still a “communist,” and I am much more so now that I was in my youth, because now my communism has been “purified” and is no longer mixed with the “Leftist” stupidities I fostered for decades. But here I intend to proceed on a strictly dialectical level, regarding only the procedural dynamic of “concrete” historical communism, and leaving aside for now its philosophical idealism of which I am a great admirer (allow me to note that in my interpretation of Marx, he is a humanist and an idealist).

3. Il comunismo: la dialettica della corruzione

Esiste un modo consueto per esorcizzare il problema della corruzione interna dialettica del comunismo, e cioè la distinzione tra “veri comunisti”, quelli soggettivamente rimasti tali, (fra i quali, se vogliamo usare questo termine trogloditico, ci sono anch’io) e “falsi comunisti”, o ex-comunisti (tipo Gorbaciov, Eltsin, D’Alema, Veltroni, Napolitano, eccetera). In questo modo, il problema della corruzione irreversibile del comunismo come fenomeno storico viene continuamente rinviato, per non scandalizzare gli ultimi babbioni credenti, che devono essere continuamente rassicurati con la teoria del tradimento soggettivo dei traditori (equivalente ateo della teoria del peccato e della debolezza della carne per i credenti). Io invece sceglierò un’altra strada. Da un punto di vista strettamente filosofico, io sono sempre “comunista”, e lo sono anzi molto più che in gioventù, perché ora il mio comunismo è “purificato”, e non è mescolato con le stupidaggini di “sinistra” con cui l’avevo nutrito per decenni. Ma qui intendo muovermi su di un piano strettamente dialettico, che riguarda soltanto la dinamica processuale del comunismo “concreto”, quello storico, lasciando perdere per ora le grandi idealità filosofiche, di cui sono soggettivamente un cultore (ricordo che la mia interpretazione di Marx ne fa un umanista ed un idealista).

The modern communism that we know, particularly in its variant espoused by Marx and the Marxists, does absolutely not originate from a spontaneous movement of the popular classes. Those who are searching for this spontaneous movement can find it rather in English trade unionism and French syndicalism (Proudhon, Sorel, etcetera). Modern communism however, has two genetic matrices (not counting Marx’s transformation of Smith’s labor theory of value) that are both one hundred percent, one thousand percent, bourgeois: the unhappy consciousness of the bourgeoisie elaborated by Hegelian theory, and the bourgeois myth of progress. I will examine them separately, but let it be clear that this is only a scholastic procedure, for in reality the two are united.

Il comunismo moderno che conosciamo, in particolare nella variante di Marx e del marxismo, non trova assolutamente la sua origine in un movimento spontaneo delle classi popolari. Chi cerca questo movimento spontaneo può trovarlo piuttosto nel sindacalismo inglese e nel federalismo francese (Proudhon, Sorel, eccetera). Il comunismo moderno (prescindo qui dalla trasformazione della teoria del valore-lavoro di Smith fatta da Marx) ha invece avuto due matrici genetiche, entrambe borghesi al cento per cento ed al mille per mille: l’elaborazione della teoria hegeliana della coscienza infelice della borghesia ed il mito borghese del progresso. Le esamino separatamente, ma sia ben chiaro che si tratta di un’operazione scolastica, perché sono in realtà unite.

The bourgeoisie, understood as a general class and not merely as the anonymous and impersonal agent of capitalist relations of production, distribution and consumption, is a contradictory class, and therefore dialectical. On the one hand, it thinks of itself ideologically as being a universal class that is the standard-bearer of wellbeing, wealth and progress for all; but on the other hand, it is aware of itself as being an exploitive class that extracts surplus labor from others, regardless of how it justifies this to itself and to those whom it exploits. This contradictory dialectical space I call the “unhappy consciousness” of the bourgeoisie, permitting myself to make use of the great souls of Hegel and Marx without their consent. The communism of Marx in particular has no relation whatsoever to the spontaneous worldviews of the popular classes of his time, instead it derives linearly from a brilliant dialectical coupling of the Smithian and then Ricardian theory of value with the Hegelian theory of alienation. All of the arguments made for the popular and proletarian origins of Marxism, including the original one made by Marx himself, are merely posterior ideological adjustments and justificatory, legitimizing mythologies.

La borghesia, intesa come classe generale, e non solo come portatrice anonima ed impersonale dei rapporti capitalistici di produzione, distribuzione e consumo, è una classe contraddittoria, e quindi dialettica. Da un lato, pensa se stessa ideologicamente come classe universale, portatrice di benessere, ricchezza e progresso per tutti, e dall’altro è consapevole di essere una classe sfruttatrice, che estorce un pluslavoro da altri, e questo indipendentemente dal modo in cui lo giustifica a se stessa ed ai suoi dominati. Questo spazio dialettico contraddittorio lo chiamo “coscienza infelice” della borghesia, e mi permetto di utilizzare senza il loro consenso le grandi anime di Hegel e di Marx. In particolare il comunismo di Marx non ha assolutamente nessun rapporto con le visioni spontanee del mondo delle classi popolari del tempo, ma deriva linearmente da una geniale coniugazione dialettica della teoria smithiana e poi ricardiana del valore e della teoria hegeliana dell’alienazione. Tutti i discorsi sull’origine popolare e proletaria del marxismo, ivi compreso quello originario di Marx, sono aggiustamenti ideologici posteriori e mitologie di giustificazione e di legittimazione.

This is particularly clear if you consider Marxism’s bovine and animal-like adherence to the bourgeois ideology of progress, which was totally nonexistent among the ancient Greeks, who were yet perfectly able to conceive of justice, equality, democracy and solidarity without this grotesque and mythological surrogate. Although the unfounded belief in progress was repudiated by a handful of “Marxists” (I site here only the Frenchman Georges Sorel and the German Walter Benjamin), their arguments never perturbed the historic site of Marxism’s age-old cultivation, which is that corpulent body of the Left that always persisted in defining itself as “progressive,” in antinomy and opposition to capitalism which it quite naturally characterized as “conservative and reactionary.” Here the world is upside-down indeed. The truth is that this so-called “progress,” which was also called “modernization,” was never anything but a sociological and ideological accentuation of the commodity form’s “liberalized” extension (beginning with the so-called “liberalization of customs” of extreme individualism). Yet in the decades following the mythical, mephitic and maniacal time of 1968, the culture of the Left became the loudest proponent of this capitalist modernization that was essentially post-bourgeois, and certainly not only post-proletarian.

Questo è particolarmente chiaro se si riflette sulla bovina ed animalesca adesione del marxismo alla ideologia borghese del progresso, assolutamente inesistente presso gli antichi greci, che erano riusciti a pensare la giustizia, l’eguaglianza, la democrazia e la solidarietà senza bisogno di questo grottesco e mitologico succedaneo. È vero che anche alcuni “marxisti” (faccio qui solo i nomi del francese Georges Sorel e del tedesco Walter Benjamin) stroncarono queste infondata credenza, ma il grande corpaccione della sinistra, luogo storico di coltivazione secolare del marxismo, si definì sempre come “progressista”, in antinomia ed opposizione con il capitalismo, tendenzialmente connotato come “conservatore e reazionario”. Il mondo alla rovescia. In realtà il cosiddetto “progresso”, chiamato anche “modernizzazione”, era sempre e soltanto l’approfondimento sociologico ed ideologico dell’estensione della forma di merce “liberalizzata” (a partire dal cosiddetto “costume liberalizzato” dell’individualismo estremo), per cui la cultura di sinistra negli ultimi decenni, almeno dopo il mitico, mefitico e demenziale Sessantotto, fu sempre l’ala marciante della modernizzazione capitalistica, essenzialmente post-borghese, e non certo soltanto post-proletaria.

The ideology of progress is based on an essentially linear concept of history, which is conceived as a symbolic space wherein you are headed Forward, and cannot go Backward. Real history, of course, does not correspond at all to this imagery for kindergarteners. An automobile on the highway can go forward or backward, but historical time is neither cyclical nor linear, it does not move in a circle according to an “eternal return,” but neither does it go forward. This stupid religion of history is falser and more absurd than the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ heaven, where tigers and lions play with children in the gardens of strictly monoracial American families (indeed, Jehovah practices Apartheid, whereas the Catholic and Orthodox God has accepted, albeit only recently and reluctantly, even mixed marriages – but not gay marriages, or at least not yet, even though political correctness is pressuring him hysterically to do so). But if you were to accept this stupid religion of history, then history would become merely a theater of winners in which the losers (in this case the communists) would immediately have to replace their defeated gods with the victorious ones. In this case it would mean replacing the Dictatorship of the Proletariat with the International Monetary Fund, replacing Eurocommunism with the European Central Bank, replacing Gramsci with Draghi and Monti, etcetera.

L’ideologia del progresso si basava su di una concezione sostanzialmente lineare della storia, vista come uno spazio simbolico in cui si è Avanti, e non si può andare Indietro. Naturalmente la storia reale non ha nulla a che fare con quest’immagine da asilo infantile. Un’automobile sull’autostrada può andare avanti o indietro, ma il tempo storico non è né ciclico né lineare, non gira in circolo con un “eterno ritorno”, ma neppure va avanti. Se invece si adotta questa stupida religione della storia, più falsa ed assurda del paradiso dei testimoni di Geova, in cui tigri e leoni giocano con i bambini nel giardino di famiglie americane rigorosamente monorazziali (Geova infatti pratica l’apartheid, mentre il Dio cattolico ed ortodosso ha accettato, sebbene da poco ed a malincuore, persino i matrimoni misti-quelli gay invece no, o almeno non ancora, anche se il politicamente corretto preme istericamente), la storia diventa il teatro dei vincitori, per cui i perdenti (in questo caso i comunisti) devono immediatamente sostituire le loro divinità perdenti con altre vincenti, e cioè nella fattispecie la Dittatura del Proletariato con il Fondo Monetario Internazionale, l’Eurocomunismo con la Banca centrale europea, Gramsci con Draghi e Monti, eccetera.

I would like to reiterate here that we are not dealing with betrayal, or at least we are not dealing only with betrayal. We are dealing with dialectics, with the severe and relentless dialectic of a theory based in Nothingness (the theory of progress). We should bear in mind that this nothingness is distinct from (but also convergent with) the Nothingness of Commodities, because the only progress that truly exists is the Progress of Commodities. This dialectic, rather than the simple formula of betrayal, can explain quite a lot about communists’ adaptation to capitalist progress.

Vorrei insistere che qui non abbiamo a che fare con il tradimento, o almeno non solo con il tradimento. Si tratta di dialettica, della severa ed implacabile dialettica di una teoria che ha come fondamento il Nulla, anche se è un nulla diverso (ma convergente) con il Nulla della Merce. Il solo progresso che esiste, infatti, è il Progresso della Merce. Questo spiega molto dell’adattamento dei comunisti a questo processo capitalistico.

Of course, we are also dealing with the proverbial “temptations” indicated by classical moralism (pleasure, wealth, power and pride). I do not deny this at all. But the explanation cannot be so banal. Yes, the majority of communists who I have personally known in half a century’s time (besides for a statistically small minority of “revolutionary ascetics”) were presumptuous, cynical and godless opportunists who were able to lead their gullible and utterly acritical followers easily by the nose (like the three-nostrilled comrades of Giovannino Guareschi, may God rest his soul). But I do not want to get lost in recounting these grotesque details of practices that were all too common. Better to get back to the severe process of the corrupting dialectic.

Naturalmente, abbiamo anche a che fare con le vecchie “tentazioni” del moralismo classico (piacere, ricchezza, potere, onori). Non intendo affatto negarlo. Ma la spiegazione non può essere così banale. Al di là di alcuni “asceti della rivoluzione”, statisticamente minoritari, la maggioranza dei “comunisti” da me conosciuti in mezzo secolo è composta di presuntuosi e cinici opportunisti senza Dio, che regnavano su babbioni del tutto privi di spirito critico (i trinariciuti di Giovannino Guareschi, buonanima). Ma non voglio perdermi in particolari grotteschi di costume. Meglio tornare al severo processo della dialettica corruttiva.

I have indicated how God’s deposition and substitution by the union of Science and History leads to an outcome that is completely nihilistic. In regards to Science, it is most certainly an ideation of enormous cognitive and practical value, it is the motor of a technological “progress” that would be foolish to deny and underestimate (and I, personally speaking, do absolutely not deny and underestimate it). Yet the value of Science pertains only to the knowledge of nature and to applications in the fields of technology and medicine, which taken by themselves are already quite significant. But no “scientific mindset” will ever be able to distinguish Good from Evil (the two words are capitalized here, of course). In regards to History, its divinization results in the utter loss of all of the ethical achievements attained by the older religion. Although the older religion postulated an anthropomorphized, transcendent deity that is nonexistent, it still contained gigantic treasures of expressiveness that can be evidenced not only in art, but also in history, in morals, and in politics.

Ho fatto notare come l’abbattimento di Dio, sostituito da un connubio di Scienza e di Storia, dà luogo ad un esito nichilistico integrale. Per quanto concerne la Scienza, essa è effettivamente un’ideazione conoscitiva e pratica di enorme valore, motore di un “progresso” tecnologico che sarebbe sciocco negare e sottovalutare (e che personalmente non nego e non sottovaluto assolutamente), ma questo vale soltanto, ed è già molto, per la conoscenza della natura e per le applicazioni tecniche e mediche, ma nessuna “mentalità scientifica” arriverà mai a distinguere il Bene dal Male (scritti maiuscolo, ovviamente). In quanto alla storia, la sua divinizzazione finisce con il perdere tutte le conquiste etiche della vecchia religione, che magari postulava una divinità trascendente antropomorfizzata non esistente, ma conteneva giganteschi tesori espressivi non solo artistici, ma anche storici, morali e politici.

Yet despite all of this, Marx still thought of himself as a forecasting social scientist rather than a philosopher (he erroneously thought to have abandoned the terrain of philosophy in 1845, at the age of twenty-seven!) Not surprisingly, the two foundational theses on which he conceived his idea of communism were both mistaken. But that’s ok, since science proceeds by trial and error, and nobody is perfect. Yet Marx’s two hypotheses were both not only slightly wrong, but both very wrong indeed. In the first place there is his mistaken conviction that the capitalistic bourgeoisie was incapable of developing the forces of production, and in the second place there is his mistaken conviction that the proletarian, wage-earning working class was capable of being a revolutionary power. We will address these two mistaken convictions separately.

E tuttavia, Marx pensava a se stesso non come un filosofo (erroneamente, pensava di aver abbandonato il terreno della filosofia fino dal 1845, all’età di ventesette anni!), ma come uno scienziato sociale previsionale. Le due tesi fondamentali su cui aveva costruito la sua idea di comunismo erano entrambe errate. Niente di grave, la scienza procede per prove ed errori, e nessuno è perfetto. Ma le due ipotesi di Marx erano entrambe non solo un po’ sbagliate, ma molto sbagliate. Si trattava dell’errata convinzione della presunta incapacità della borghesia capitalistica di sviluppare le forze produttive, in primo luogo, e dell’errato convincimento sulla capacità rivoluzionaria della classe operaia, salariata e proletaria, in secondo luogo. E trattiamole separatamente.

How did Marx ever get the idea that the bourgeois-capitalistic class (whose two elements he does not discern) would become incapable, after a certain point, of continuing to develop the forces of production? I don’t know how, but I can hypothesize that it was due to an erroneous historical analogy. Historical analogies are more misleading than mirages in the desert. Having considered how the classes of ancient slave-owners, feudal lords and Asiatic despots had all become incapable, at a certain point in their economic development, of further developing the forces of production, Marx inferred (in a typical case of induction) that the same would hold true for the capitalistic bourgeoisie. This forecast was mistaken. The capitalistic bourgeoisie is in fact a class unlike any other that came before it; it is an anonymous historical agent of production for the sole sake of production itself, which means for the sake of a production that is limitless. And to think that Marx actually did begin to notice this anomalous fact in other parts of his writings! He noticed it, but he did not draw from it the logical consequences.

Come è venuto in mente a Marx che da un certo punto in poi la classe borghese-capitalistica (da Marx non distinta nei suoi due elementi) si sarebbe rivelata incapace di continuare a sviluppare le forze produttive? Non lo so, ma posso ipotizzare che si sia trattato di un’errata analogia storica. Le analogie storiche sono ancora più ingannatrici dei miraggi del deserto. Dal momento che le classe dei padroni schiavistici, dei signori feudali e dei dominanti asiatici si erano effettivamente mostrate ad un certo punto dello sviluppo economico incapaci di sviluppare le forze produttive, Marx ne inferì (tipico caso di induzione) che lo stesso sarebbe successo anche per la borghesia capitalistica. Previsione errata. La borghesia capitalistica non è una classe come le precedenti, ma un agente storico anonimo della produzione per la produzione, e cioè per la produzione illimitata. E pensare che in altre parti della sua opera Marx sembra accorgersene. Se ne accorge, ma poi non ne tira le conseguenze.

As for the proletarian, wage-earning working class’s capacity for being an inter-mortal revolutionary power, it should be noted that Marx never actually spoke of this. Instead, he spoke of the formation of an associated, cooperative and collective worker that included everyone from the manager down to the last unskilled laborer. Yet this Marxian thesis (hidden in the unpublished Chapter VI of Capital, and this is not by chance) was completely ignored by the entirety of real existing “Marxism,” which always identified as its revolutionary subject the class of wage-earning factory workers. Now, if you know factory workers at all (and living as I have in Turin, you couldn’t help but know them!) then you know that without the mediation of political parties, labor unions and bureaucratic experts they wouldn’t be able to organize even a bowling club or a fishing trip, and this is not by chance. Whereas artisans and peasants possess mastery of their professions’ autonomous production techniques, workers are inserted into a production process that is completely extraneous to them and to which they do not possess the “keys” to autonomously self-manage (except in a few irrelevant cases).

In quanto alla capacità rivoluzionaria inter-modale della classe operaia, salariata e proletaria, va detto che in realtà Marx non ha mai parlato di essa, ma della formazione di un lavoratore collettivo cooperativo associato, dal direttore all’ultimo manovale. Ma all’atto pratico l’intero “marxismo” veramente esistito di fatto ha ignorato questa tesi marxiana (nascosta nel Capitolo VI del Capitale, e non a caso “inedito”), e per soggetto rivoluzionario ha sempre inteso la classe degli operai salariati di fabbrica. Ora, chi li ha conosciuti (ed abitando a Torino non si poteva non conoscerli!) sa che la classe operaia senza mediazione dei partiti, sindacati ed apparati tecnici non potrebbe gestire neppure una bocciofila o una società di pesca con la lenza, e questo non a caso. Mentre infatti gli artigiani ed i contadini sono padroni delle tecniche produttive autonome della loro professione, gli operai lavorano sulla base di un processo produttivo a loro completamente estraneo e di cui non posseggano le “chiavi” per la autogestione autonoma (salvo irrilevanti eccezioni).

Now, it is a terrible thing indeed to base your cause on three presuppositions that each turn out to be nonexistent: (1) the myth of progress, which does not exist; (2) the incapacity of the capitalistic bourgeoisie to develop the forces of production, which does not exist; (3) the capacity of the proletarian, wage-earning working class to be a revolutionary power, which does not exist.

Ora, è terribile fondare la propria causa sulla base di tre presupposti tutti e tre inesistenti: (1) il mito del progresso, che non esiste; (2) l’incapacità della borghesia capitalistica di sviluppare le forze produttive, che non esiste; (3) la capacità rivoluzionarie della classe operaia, salariata e proletaria, che non esiste.

The reasons for communism’s corrupting dialectic are to be found in these three nonexistent presuppositions, and definitely not in Gorbachev’s ambition to advertise Louis Vuitton bags and Pizza Hut, or in D’Alema’s desire to strut about on his sailboat like every good capitalist or any hospital Chief of Staff. That is just colorful folklore for fools. Yet the depths of “corruption” have to be probed still further in order to attain a genuinely dialectical understanding of it. By probing these depths we can move well beyond the moralistic illusion of corruption entertained by the irrecoverably subaltern junior staff.

Le ragioni della dialettica corruttiva del comunismo sono queste, e non certo Gorbaciov che ambisce a pubblicizzare le borse Vuitton e la pizza Hunt o D’Alema che vuole pavoneggiarsi su di una barca a vela, come ogni buon capitalista o primario d’ospedale qualsiasi. Questo è solo folklore per straccioni. Ma il tema deve ancora essere approfondito, per poter avere della “corruzione” una comprensione dialettica, e non solo l’illusione moralistica per subalterni irrecuperabili.

I repeat, once again, that I am using the term “corruption” here in the dialectical sense to signify an internal process in communism’s historical dynamic (but I should not tire of repeating myself, since I am going against the current of common sense in order to effect a radical, qualitative “conversion” of the current mindset, which anthropomorphizes and is itself anthropomorphized). In saying that communism was corrupted from within my intention is simply to indicate a historical process, and not by any means to defame the Marxian idea of communism (I, at the age of sixty-eight, declare myself to be a “communist,” and it is unlikely that I will change my allegiance in the time I still have left to live). This dialectic of corruption became historically enmeshed with the dialectic of limitlessness of capitalist expansion. Thus the intimate and profound philosophical meaning of the last thirty years of humanity’s history can be put into words: for the time being, limitlessness has won over corruption.

Ricordo ancora una volta (ma non devo stancarmi, perché vado controcorrente contro il senso comune, e pretendo una “conversione” radicale qualitativa della mentalità corrente, che è antropomorfica ed antropomorfizzata) che uso il termine “corruzione” nel senso dialettico di un processo interno a una dinamica storica. Dicendo che il comunismo si è corrotto dall’interno intendo connotare un processo storico, non certo diffamare l’idea marxiana di comunismo (io stesso, a sessantotto anni di età, mi dichiaro “comunista”, ed è improbabile che cambi connotazione nel tempo che ancora mi resta da vivere). Questa dialettica di corruzione si è storicamente intrecciata con la dialettica di illimitatezza del processo di allargamento del capitalismo. Possiamo così definire il senso filosofico intimo e profondo dell’ultimo trentennio di storia dell’umanità: per ora l’illimitatezza è uscita vincitrice della corruzione.

So now what?

E adesso?

***

4. Open and Provisional Conclusions: from the World of Illusions to the World of Understanding

Illusions have been socially necessary in history, from the illusion of the promised coming of the kingdom of God (Paul of Tarsus) to the illusion of socialism’s sure victory over capitalism (Lenin). This fact needs to be understood, regardless of the little smiles it may bring to disenchanted faces. But the time for cultivating illusions is now over, and it seems to me that it will not return. From now on the dialectic of illusions needs to be replaced by the dialectic of understanding.

4. Conclusioni aperte e provvisorie: dal mondo delle illusioni al mondo della comprensione

Le illusioni sono state socialmente necessarie nella storia, dall’illusione dell’avvento prossimo del regno di Dio (Paolo di Tarso) all’illusione della vittoria sicura del socialismo sul capitalismo (Lenin). Occorre capirlo, e non solo fare sorrisini di disincanto. Ma il tempo della coltivazione delle illusioni mi sembra ormai passato irreversi-bilmente. D’ora in avanti bisogna sostituire alla dialettica delle illusioni la dialettica della comprensione.

Taken as a whole, the inheritance left to us today by a century and a half of Marxism is obsolete, with the exception of a few, rare high points. You cannot pass from idealism to positivism without paying a price – not even if you are passing from Marx’s radically modified idealism to Engels’ positivism. As cases in point, there are those who believe that the current trend towards globalized capitalism, rather than being a moment in capitalism’s limitless development, is merely a “response” to the cycle of struggles waged by the Fordist working class for wealth redistribution in the 1960s. There are also those who continue to think that the crises of capitalism are only due to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, or to imbalances between overproduction and underconsumption. These features are certainly present in, and relevant to current capitalism, but they are superficial features. The “profundity” of the matter does not reside in them, but in the tendency to limitlessness of the expansion of the commodity form.

Presa nel suo insieme, al di là di alcuni rari punti alti, l’eredità che ci lascia un secolo e mezzo di marxismo è ormai obsoleta. Non si passa dall’idealismo, sia pure radicalmente modificato da Marx, al positivismo di Engels senza doverne pagare il prezzo. C’è chi crede che l’attuale tendenza al capitalismo globalizzato, anziché essere un momento del suo sviluppo illimitato, sia stata soltanto una “risposta” al ciclo delle lotte rivendicative per la distribuzione della classe operaia fordista negli anni Sessanta del Novecento. C’è chi continua a pensare che le crisi capitalistiche siano soltanto dovute alla caduta tendenziale del saggio di profitto, oppure a squilibri fra sovrapproduzione e sottoconsumo. Questi aspetti sono certamente presenti e rilevanti, ma sono aspetti di superficie, perché la “profondità” non è questa, ma è la tendenza alla illimitatezza dell’estensione della forma di merce.

The understanding that replaces illusions must be based on the two previously discussed dialectical dynamics being fully conceptually assimilated to each other, whereby the limitlessness of capital and the corruption of communism are seen as parts of a single process. By “communism” here I obviously do not mean the communist idea, with which I fully identify, but real existing twentieth-century communism. Once these two dialectical dynamics have been assimilated, nothing is yet resolved, but at least the road is cleared of debris and a vehicle may proceed without getting hindered or stuck.